Hooks and Ink: Life’s Illusions and the Pursuit of Truth

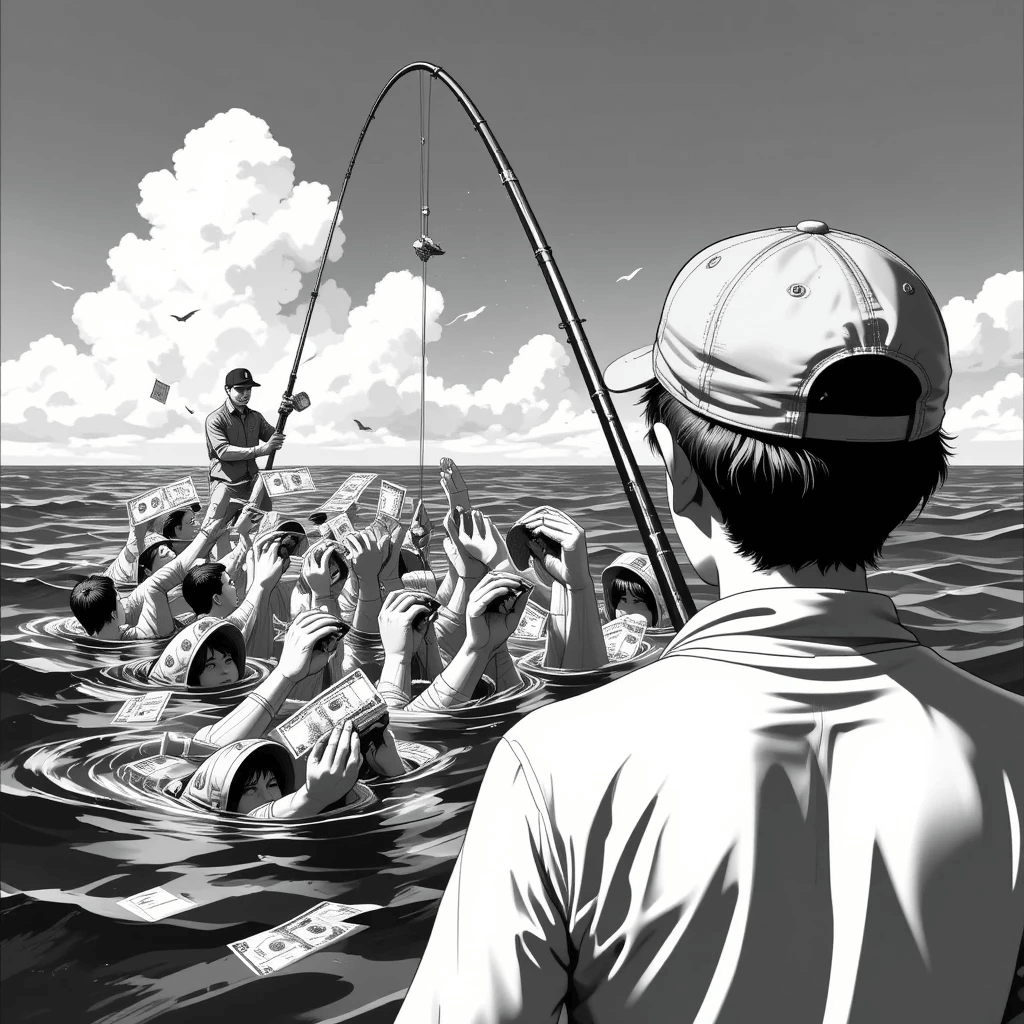

One: The Lottery Hook

(The parallel between fishing and the lottery business, exploring how people are lured into financial traps.)

One guy in the evening gave a look to Einstein while crossing over the restaurant. It was tea time. Einstein waved at him.

“Entha vallarkkum kittiya?” he asked about the lottery winnings.

After two minutes of friendly talk, he came with Einstein into the shop and bought two lottery tickets. The eye-catching business always seemed like fishing to Einstein. This lottery was one of them. While preparing for fishing, his father always put a thing called “minusam” with the hook. It was a piece of fluorescent cloth. It emitted light and mimicked prey to the fish. Once the fish thought it was food, it would bite. This was how, inside the ocean, his father caught fish. When Einstein went fishing with his father at night, the first shock to him was the hook without real prey—just “minusam”. His father slowly taught him how to release the rope with multiple hooks, and he did it carefully. Suddenly, he felt something pulling his rope inside the ocean. So he pulled the rope to the boat. Three fish were caught on the six-hook roll. The first fish jumped from his hand while he was unplugging it from the hook. So his father taught him another lesson—how to break the neck of the fish after unplugging it. Otherwise, it would escape, mix up all the rolls, or jump until it died, making noise in the boat—distracting him from the next catch. So it was better to break the neck. Einstein successfully broke the necks of the other two fish. Lottery was “minusam” in the Middle East due to the speed money they expected—and that their families and hometowns expected from them. So they bit. Sometimes, big fish came and ate the hooked fish before the fishermen could take all the fish into the boats. Like his father, the lottery owners took all the Middle Eastern labor camp fish. The shops that sold the tickets were the big fish, sharing a little fish flesh while they hooked. The whole life seemed like a waste to Einstein. People always ran for money. Some people used this opportunity and pumped money from these people.

What is money?

He didn’t try to find the answer to this question. But he knew he wanted a little more—like everyone else.

How much is this “little more”?

It was another question Einstein didn’t have an answer to, and he didn’t try to find out. Instead, he put his glass water bottle upside down on the restaurant table. The lemon tea inside revolved in circles, and the lemon seeds, along with tiny juice-filled sacs, slowly fell from the top to the bottom. He thought, what if the world suddenly became upside down like this? The restaurant would fall into the sky. He too. Everyone, too.

The biggest millionaire in the world. The most popular person in the world. The poorest in the world. The innocent, as well as the most criminal. The sane and the insane. All would fall slowly, like the lemon seeds, into the sky. But no one would see the scene from the outside, as everyone would be falling. So that moment would not be captured by anyone. And it would not be posted on social media by anyone. An ideal shot of the world. At that moment, Einstein started thinking—he was not the center of the world. The problem was, like him, no one could live in the world as it was. Because the only possibility of living in the world was by making your own world inside your head. It would change with your understanding of it. It would end with you, without any remains—like you. Maybe it will remain. Who am I to tell you the facts of the world? God? Yes, he knew even the idea of God could be fake. But Einstein called on God when he was helpless and in downfall. It was a childhood teaching from his family. They were poor and placed their hope in an imaginary character—one that was an approved god in the world.

Like other poor families, they traveled with hope. Not to see God at least once in their lives, but to survive and manipulate their minds into believing that if no one in the world would help them, this imaginary character would. Because they were very sure the first thing would happen for sure. So it was better to keep a backup.

Durr…Burrrr….Dur…Durr…. The music and rhythm.

Everyone laughed. Why? Because it came from one guy’s buttocks. A fart. As he was leaving the room and closing the door behind him, he let out another Durr…Burrr..Dur.Durrrr. Two Black guys and Einstein inside laughed out loud. The farter was the two-angled-eyed, focused man from the previous chapters (Click here to read about his story) . He had become a funnier dude in the labor camps now.

Anyway, nobody liked the smell, so they ran away—laughing.

Two: The Ink of Memory

(A reflection on the importance of pens in Einstein’s life, connecting it to his childhood, education, and fishermen’s way of life.)

The unusual extra two pens in the monthly items at the institute surprised the two guys. Their boss had bought them without any reason. Einstein believed it was a symbol of allowance for his literature and a way to support their personal growth or self-learning during free hours.

Einstein thought about the pen—it was a symbol throughout his life. He gifted pens to people he liked, especially those he enjoyed having literary conversations with or whose writings he admired. Some people also gave him pens.

It started in childhood at the local government school in a fishing village. They conducted a quiz competition—actually, two. One was about Indian independence; the other he doesn’t remember well now. But there were two quiz competitions. The teacher had given all 50 questions and their answers to be memorized. From these 50 questions in each quiz, they would ask 25.

His aunt, the only literate person in the whole family (though she had failed 10th grade but studied up to that level), trained him in the evenings. Actually, he wanted her to check whether he was answering the questions correctly or not. Unexpectedly, a strange interest grew in him, and he memorized all the questions after his evening cricket games with friends on the beach. The next day, during the quiz, whenever the quiz master announced a question, Einstein saw its answer in front of his eyes. Though his friends copied some of his answers, the quiz master announced Einstein as the final winner in both competitions, scoring full marks. He received two pens during the Independence Day celebration in front of all the students. Although pens made a big impact on his life, as a boy from the fishermen community, his childhood idea of a pen was different. His parents once pointed to a fish inside a small boat, caught by his father, and told him—”Kadal pena” (sea pen).

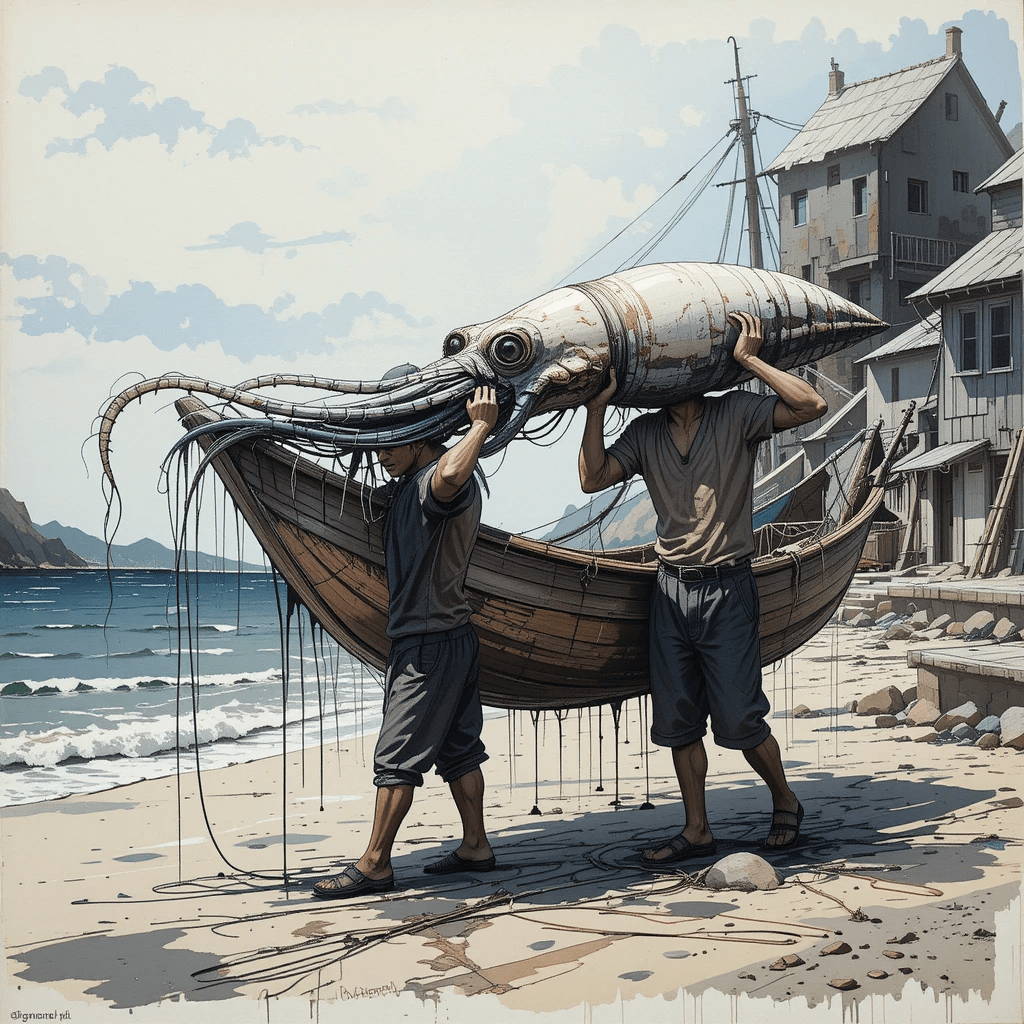

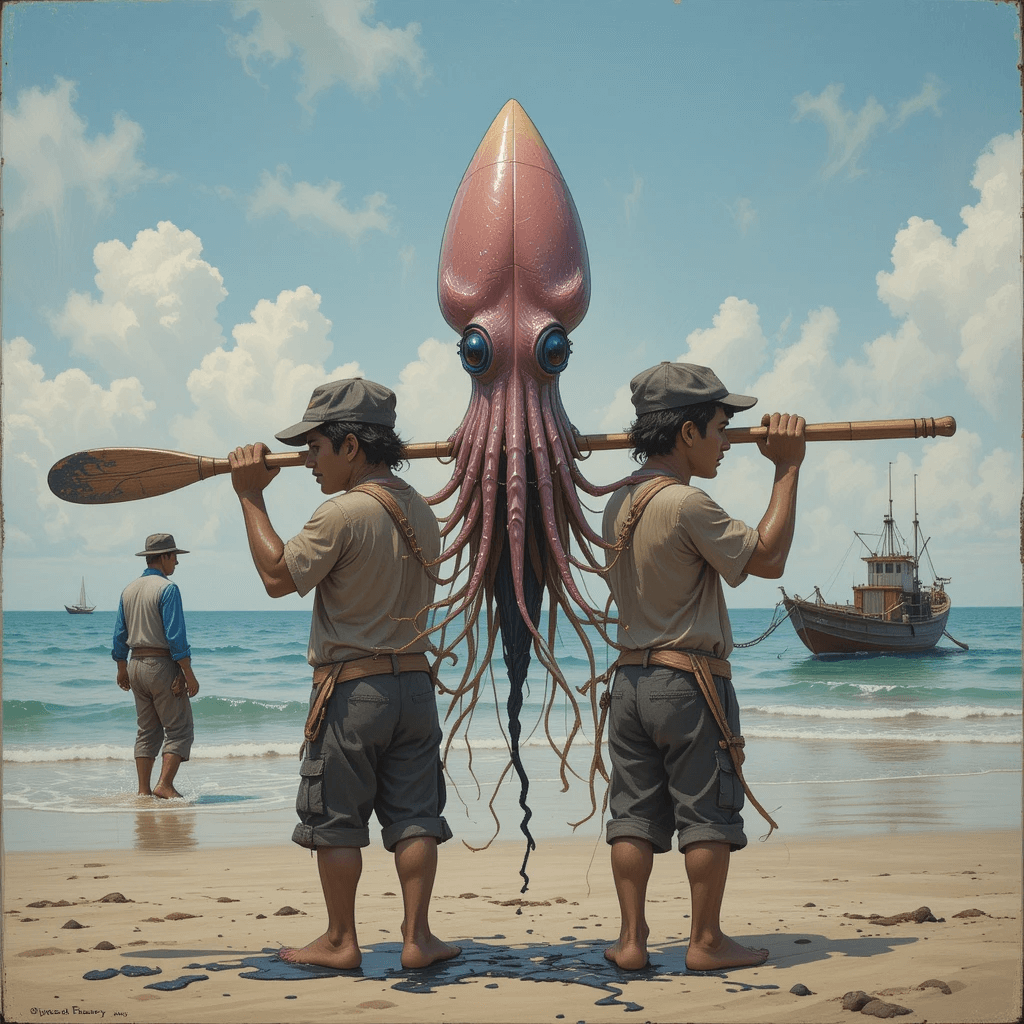

It was a squid—the one that releases ink whenever it is attacked or in trouble. Einstein didn’t like squids releasing ink; it always made his clothes dirty. His father would bring home squids in a fishing net bag. After reaching the wharf, Einstein and his brother would carry the bag using a long stick called ‘tholava’ in the coastal language of Kerala. This stick was also used to push against the water in case the mechanized propeller had any issues in the ocean. Einstein and his brother would stand at the front and back of the tholava, with the squid bag hanging in the center. As they walked, it would oscillate from side to side, spilling ink and staining their clothes.

In school, whenever he saw excess ink from a pen, Einstein would recall those squid memories. But it wasn’t just squids. Every fish his father caught in his tiny boat carried an interesting story with it. And all those stories were connected to Christian saints who had once visited Kerala or had ties to the sea.

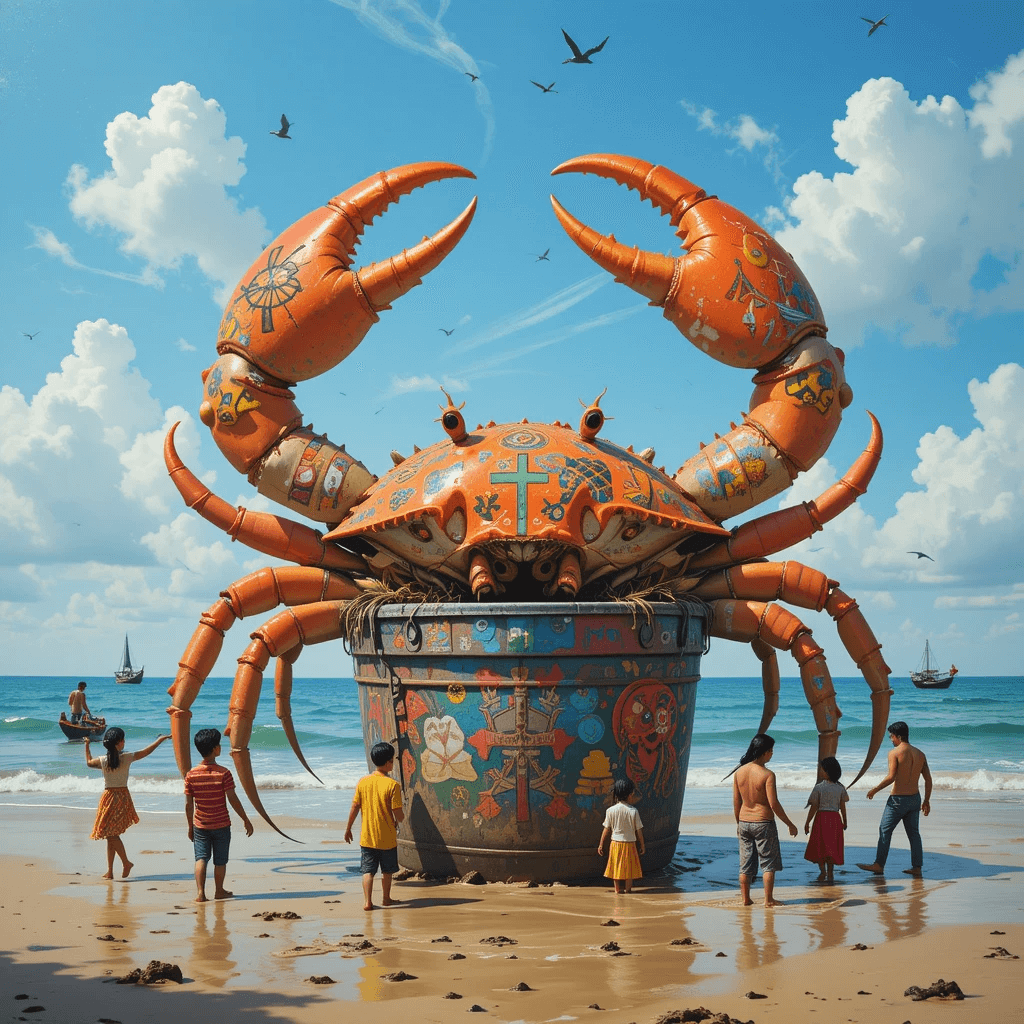

The Story of the Giant Crab

One afternoon, Einstein’s father caught an unusually large crab. When he brought it home, the entire family and the neighbors were astonished—it was enormous. When unusual things happen in life, people often become confused about what to do next. So, the whole family and their well-wishers sat around the crab, wondering what should be done with the giant creature. Some suggested selling it at the coast, but others argued that the local traders would offer a lower price. Selling it in the market might fetch a better price. But how much was it really worth? No one could estimate. What if it was worth more than they imagined? There was a possibility, Einstein’s father agreed. The crab was still alive, kept in a large bucket filled with seawater. It struggled to move, its powerful pincers scraping against the plastic bucket, but unable to gain a grip. Einstein, his siblings, and his friends gathered around, curiously watching this strange new creature, while their grandmother scolded them, warning them to stay back and not put their hands inside. The crab was dangerous. But, as children often do, they ignored her. Suddenly, Einstein noticed strange patterns on the crab’s shell. Since it was common in the region to find naturally formed markings resembling religious symbols, the kids excitedly pointed out a large cross shape on its back. They showed it to the elders, and that’s when Einstein’s father told them a story.

It was from a time long before history was written. A saint named Andrew was traveling from Portugal to Kerala. During his voyage, the ship encountered terrible storms. As the ship fought against towering waves, Saint Andrew’s prayer chain—one with a wooden cross—slipped from his hand and sank into the deep ocean.

He was devastated. The chain was not just valuable; it was sacred. With it, he could pray better and seek divine protection. But despite the misfortune, he pressed forward, guiding the ship through the fierce sea.

The next morning, as the storm began to calm, something miraculous happened. From the depths of the ocean, the chain began to rise. As Andrew looked closer, he saw that it was being carried by a giant crab. The massive creature emerged from the water, holding the sacred chain between its pincers.

Saint Andrew took it back with immense gratitude and prayed to God to calm the sea. God listened to his prayer, and the waves became still. In gratitude, Andrew blessed the crab and marked a cross on its shell. From then on, through generations, this mark was passed down to its baby crabs, becoming an ancestral symbol. Back at home, after listening to the story, the kids picked up small sticks and playfully tested whether the crab could cut them with its pincers. After some time, one of the family members suggested selling it to a resort in the village. Tourists loved seafood, and a giant crab like this could fetch a high price. It seemed like a good idea to everyone.

What if it was a rare one? Until you know the real worth of something, your imagination can take it to the skies. An hour later, Einstein’s father and his friend returned—with the crab. The resort had offered an even lower price than the coastal market. That evening, the family cooked the crab, and Einstein’s mother prepared a rich, flavorful curry. The entire family, along with the kids, sat together and enjoyed the feast. Years later, after becoming an adult, an immigrant, and a traveler, Einstein realized how luxurious his life had been when he was just a fisherman’s son—before he let the world of technology and capitalism into his life.

Three: The Bad day and Goatman’s Dream

(Einstein’s contemplation of leaving behind human betrayals to live a simple life with nature, particularly through goat farming.)

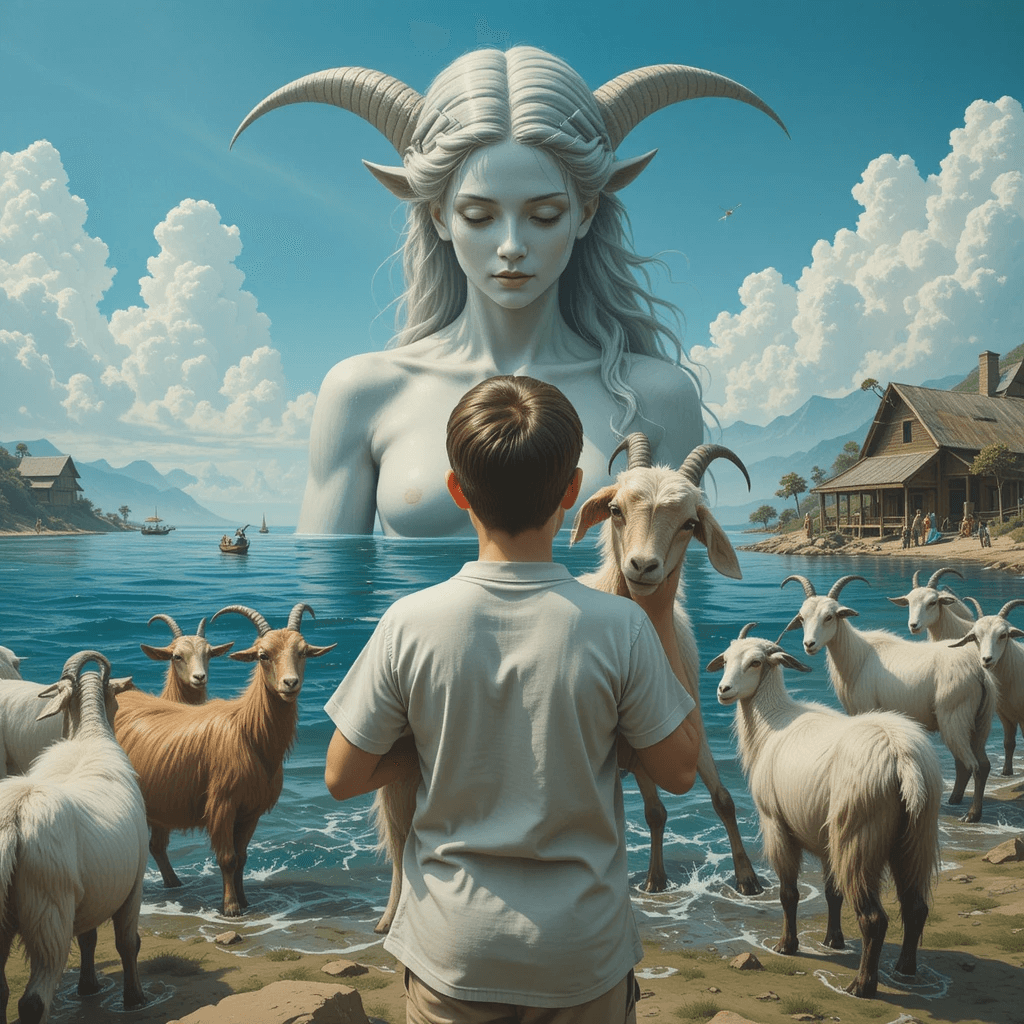

In his imagination, Einstein visualized a goat farm. After years of spending time with people who broke his trust, he desired to spend more time with animals and kids—living beings not intelligent enough to break his trust. Or, we can say, innocent beings. Actually, it was his business idea to farm goats so that he could earn food directly from nature. He was not lazy and was determined to work hard. So he visualized himself working on his idea—farming goats, taking care of them, studying their behaviors, and speaking to them whenever he felt cringed about his past. There were many benefits to this lifestyle, one he liked to live. And he read books while they were sleeping.

His parents lived a life like this—a life directly connected with nature. His father caught fish from the ocean. After learning in school that the ocean covers two-thirds of the globe, Einstein was always amazed by his father’s talent. His father used a tiny hook inside this vast ocean, yet he knew exactly where to sink it, even without bait, and still managed to catch fish. In childhood, Einstein and his friends believed that his father and other fishermen met a giant superhuman in the ocean. It was a woman, bigger than buildings. They called her ‘Kadalamma.’(Sea Mother) She would rise from the water after the sun sank into the ocean in the evenings, and the fishermen would give her their lists, just like Einstein gave his list to the grocery store every day. But his father didn’t know how to write and never asked Einstein to make a list of fish on paper. like his mother did every week. Maybe his father spoke a foreign language that nobody else knew—only the fishermen and Kadalamma understood it.

Sometimes, during busy times, fishermen dropped their paper lists into the ocean, losing them to the depths. So they returned to shore without fish. Some days, the rain washed away their lists. Some days, cyclones came and took the paper away—sometimes even the fishermen. When that happened, they never returned. Einstein’s friend’s father was taken away by a cyclone. His friend only saw his father’s face on the last evening when they pushed their boats into the ocean.

But after growing up, Einstein and his friends realized that the Kadalamma was just a children’s story—with deep truths hidden within. Anyway He understood his father’s brilliance in knowing exactly where to sink the hook in the vast ocean, allowing him to return with more fish in the morning. But his father didn’t farm fish. Maybe he did, in a way—by not harming Kadalamma, only hooking the fish he needed in his tiny boat and leaving the rest of the ocean untouched. It was an artisanal way of fishing, conserving the ocean.

Like his ancestors, Einstein wanted to be a goat farmer now. Life in the universe started in the ocean with fish, which evolved into goat-like animals, and eventually into humans. So Einstein wanted to evolve his family’s roots—from fishermen to goatman.

The one thing Einstein could do that his ancestors couldn’t was read in his free time and document his work. That was something his father couldn’t do. As His father was a natural man—he biologically fell in love with a woman, built a family, experienced every amazing thing with his senses, and kept those memories in his heart and brain. Neither his family nor his wife’s family had the privilege of education, so they hadn’t been influenced by literate snobs; they lived fully with their hearts in this world. They supported each other, so they never understood the concepts of mental health and depression. Just like rich people say, “Money is not important in life.”

Unlike his parents, Einstein’s life was trash. Even in his own imagination, people laughed at him. But, as always, he studied people when they laughed at him. He noticed that some people weren’t truly laughing but only pretended to, just to fit into the group. They had never truly expressed their emotions—living a life where their feelings were artificially created, just to avoid embarrassment.

All these visualizations came to Einstein’s mind during one of his many resignation decisions. His entire life, he tried to prove he was talented, but he was exploited by many business people. So he left places whenever he felt insulted or chained. Some of his office acquaintances labeled him an idiot, while others called him brave. But none of them ever left their jobs—only he did. Then he traveled. He faced consequences. And ironically, despite all his decisions, his life moved backward instead of forward. He struggled a lot, was insulted even more, and voluntarily let himself be chained. Eventually, he realized there was no point in anything. At any minute, he could die. He thought about what would happen if the world suddenly turned upside down and everyone fell into the sky. Nothing lasts.

He remembered something his friend had told him about food. Food is actually free in this world. Nobody owns the earth. Food grows from the earth, and whenever you find it on a tree, you can eat it. But the system had collapsed completely, and people died of hunger, even though they had the intelligence to find food and the strength to pick it.

Being from a fisherman’s family and going fishing, he felt proud because, in his life, he had the chance to live in harmony with nature.

So he thought of farming goats now. At least he could grow his own food. He lost the chance to learn fishing and build the physical ability required for it because his father sent him to school, hoping at least one person in the family would be literate—someone who would bring pride to the community.

So Einstein became a journalist. But after realizing the journalism world was full of lies, he left. Actually People never truly let him in. And He escaped from that noise—or maybe he had planned to escape all along. Just like his mother. She didn’t like TV. It always disturbed her sleep. But as a child, Einstein fought with her over it. He shouted at her whenever she turned down the volume or switched off the TV while he was watching cartoons or the Discovery Channel. As a child, he never understood why his mother always wanted silence and sleep. But now, he understood very well—why he, too, craves silence and sleep.

Four: The Inescapable Cycle

(A reflection on Einstein’s journey through life, from his fisherman roots to becoming a journalist, only to realize the world operates on lies and illusions.)

The idea of God seemed very different to him in helpless times. He thought about superstar Rajinikanth and A.R. Rahman—the two people he admired. But whenever they credited God for their victories, he disliked it. However, now he understood. People often have no support, and only they know the worth of receiving a blessed opportunity. Arrogance, he realized, always comes from the privileged—those who have a safety net when they fail—or from those who blindly follow the words of these privileged groups without question.

God is the belief of the poor and the helpless. Einstein never went to church. But one day, his mother asked him to go. “This one time, listen to me, son. God will bless you,” she said. At that time, Einstein had been betrayed by many. He was struggling with an identity crisis, unemployment, crushing debt, and an overwhelming sense of inferiority. He was alone.

Even in that situation, his mother’s words didn’t make sense to him. He had read too many philosophical books in college and throughout his life. He fully understood how religious institutions took advantage of the helpless, exploiting their faith in an unknown symbol—God. The poor clung to the belief that a supernatural force would bring them justice because they were too weak to fight for it themselves. First, the priests profited from this belief. Then, the politicians followed.

Despite his knowledge of societal manipulation, he decided to go to church that day—just to listen to his mother. He had listened to many people in his life. They had betrayed him. Most of what they said was idiotic. But he had listened anyway. So why not listen to his mother, just this once?

And surprisingly he got a free lunch from the church that day.

Sometimes, listening to mothers is good for our lives.

The next day, he got a new job.

Now, Einstein didn’t fully understand the language of life and nature—but his belief in hard work grew stronger. If one sincerely dedicates themselves to their work, one day, things will change in their favor. Arrogance and superiority complexes are useless. Great people like A.R. Rahman and Rajinikanth attribute their success to their idea of God. Suddenly, Einstein realized their God was not tied to a specific religion—it was simply connected to their victories. It was an eye-opener for his new life.

He learned to put aside his superiority complex and give credit where it was due. Because life is just an imaginary thing, and if you try to grow, it will always humble you.